This article comes from guest blogger, Abbi Wonacott. Thanks!

As early as the 1910’s, Japanese men were recruited to come and work at the Eatonville Lumber Company. These men labored worked hard and embraced their little town beneath the great mountain. Soon, these men brought their Japanese wives and raised their children here. Many of their children were born in Eatonville and were American citizens. Those of Japanese descent worked right along side other mill workers for the same pay.

“The Japanese lived in make-shift shacks because most were not allowed to own their own houses. Their homes were clean and orderly with beautifully kept yards. The kids used to marvel as even the dirt was raked in front of the homes. The Japanese kept to themselves and never were about town much at all. They went to work for the Eatonville Lumber Company and only shopped at the company store next to the mill.” (Brown)

In 1915, Japanese men demonstrated their love for the town as they rushed into the burning hardware store and removed the dynamite stored in the back.

The Japanese enjoyed life in Eatonville and working for the Lumber Company. The company even sponsored a winning baseball team.

Japanese children attended Eatonville schools where they learned and played together with the white students. It made no difference that they were Japanese. Many Japanese were class representatives, ASB officers, and school athletes.

The Japanese were involved with the town of Eatonville but still maintained traditions. There were sumo matches, a community hall, Japanese school, and even printed their own magazine. “Even in a remote lumbering mill camp like Eatonville, Washington, the Japanese community managed to publish a coterie literary magazine, Kyomei meaning Resonance (Kumei).”

Pearl Harbor Attack

Then, the unthinkable happened: Attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. On a Sunday, the Nation of Japan executes an attack of a navel base with thousands of unsuspecting American military bringing the death toll of 2,390.

Because of the practice of sending Japanese children to Japan for a few years to strengthen culture and existing close family ties, all people of Japanese descent are deemed suspect.

Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, “State Patrolmen searched the homes [in Eatonville] of the Japanese and took away all firearms, some of which were stored in the town hall for a long time.” (Engal).

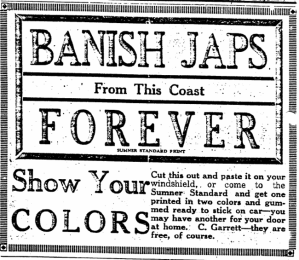

Though many in Eatonville thought the Japanese were good people, in the town of Sumner anti-Japanese feelings were reaching dangerous levels. (See poster below.)

Fear and treats of retaliation from out-of-towners and a newspaper headlines warning of additional attacks on the west coast, prompted a feeling that maybe the Japanese would be safer if they left.

Then, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which stated that Japanese even those born in the US must leave the west coast and report to internment camps. They were only to bring two suitcases and whatever else they could carry. All household items, keepsakes, heirlooms were left behind.

The Order sanctioned the removal of all Japanese to “camps of concentration,” as Dispatch Publisher Eugene Larin wrote at the time. Children, elderly, infants, none was allowed to remain in their various communities. It mattered not if the people were American citizens or loyal to the United States. They lost everything but the clothes on their backs and the few belongings they could carry. People were given 48 hours to prepare for this terrible experience.

May 16, 1942

May 16, 1942: the day the Japanese were taken from Eatonville, Wash. The sound of many, large Army Transport trucks were heard coming up the hill. The massive trucks with large wooden slates and no cover blustered down the road to where all the Japanese families lived. The Japanese were hastily loaded. As the loud trucks roared out of town and down the hill, the Japanese looked at all those watching. Both could only stare. “The children were stunned; in shock. The homes still had most of the Japanese families’ belonging since they were only allowed two suitcases per person. All else was left behind. An Eerie site.” Lois Daly Brown

The Japanese children and all the other children of Eatonville knew each other as they went to classes and played sports together. Lois Daly Brown was shocked as all of her Japanese schoolmates were gone: Teddy, Bobby, and all the well-kept little girls, gone. “Teachers were crying and the children kept asking why; what happened? Many adults would not or could not talk about it for days.”

Brown stated that Japanese were such good people and it was a horrible, dark day she remembers clearly 69 years later (Brown).

There are about 62 men of Japanese origin employed by the Eatonville Lumber Co., of whom almost exactly half are American-born citizens, a number of them born in Eatonville and lived here all their lives. The mill workers among them are members of the Lumber & Sawmill Workers Union.”

Eatonville’s Japanese settlement has been here for about 30 years. About 100 Japanese, including women and children, were here recently. The maximum at any time was about 150, it is stated (Dixie Walter).”

Then [they] rounded up like so many cattle and, in our area, sent to the Puyallup Fairgrounds where some military genius with a perverse sense of reality named the place of heartache, Camp Harmony (Dixie Walter).

June 5, 1942

Excerpt from Chet Sakura’s first letter to the Eatonville Dispatch June 5, 1942.

. . . Camp Harmony is directly under the Wartime Civilian Control Authority (WCCA) Supervision, with details carried out by our own camp staff. Chief of Staff is the well known editor of the Japanese American Courier, James Y. Sakamoto. Under him is a capable staff and many workers among which, of course, are many Eatonville people. We police the camp with our own police force and among them are Mack Nogaki, Isa Saito, Kaz Naito, and Ken Nogaki.

“In the kitchen clean-up crew we find a number of Eatonville Hi boys, Pete Yoshino, Hiroki Hosokawa, Taro Kawato, and Mas Kudo, and of the others there’s Sumitani, Nakatani, Hashimoto, and Takeda (Setter).

Everybody gets in and digs here, in even the lowest jobs. In the children’s mess hall, I found Jerry Kurose, the head dishwasher, with Shorty Nozaki his assistant. Of course all the sanitation and general maintenance is kept up by our own crews and we find Sam Kumata one of the foremen of a work crew.”

One group of 200 left for Tule Lake, Calif., last week, among them Ken Nogaki, Kaz Naito, Tak Yamaguchi, and Eddie Nakamura. Another group of 13 left for the Montana beet fields, with them Jack Nagaoka and family. They left as a trial group and reports are so favorable that more are going soon. Howard and Alice Sakura and Mack Nogaki have signed to go with the next group. We’re all anxious to be permanently settled and view each announcement with great interest. Well, there’ll be more next week, with additional details of work and recreational programs, so, until then, Your correspondent, Chester Sukura

P.S. – I just received the Dispatch this evening and it seems strange to see my letter in there. It seems as though I should be there in Eatonville, helping with the local war efforts, but I guess I just have to wait now. But my hopes and wishes go with your efforts.” (Walter).

June 12, 1942

In the June 12, 1942 issue of the Eatonville Dispatch, Sakura writes:

We have had a few visitors from Eatonville and all of us certainly enjoyed the visits. Fred Roeder and family visited last Sunday and brought some household goods to us. They also brought a few flowers that were greatly appreciated. After having a garden full of flowers, we certainly miss them and tell any other visitor that flowers will be very welcome.

“Butch” Snyder dropt [sic] by and we saw Ray Nadeau and family at the gate too. It seems strange to see people outside the gate wanting to get in and people inside wanting to get out, all for the mutual interest of friendly visits. We wonder which side of the gate is which and why there should be a gate there with so many visitors. There are visitors at the gate at all times and on Saturday and Sunday, the gate is jammed. All this indicates that the American people are the friendliest people in the world and makes us all feel good inside.

June 18, 1942

June 18, 1942: “It’s rather hard to start a letter this week after reading in the Dispatch of another Eatonville casualty in this war. I knew Chuck Biggs well (killed in action in Alaska at Dutch Harbor during the Japanese attack there on June 3. He was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Biggs, Sr.) well and saw him grow from a little lad like my boy, to be a soldier. And now, as those close to us make the supreme sacrifice, we feel more determined in doing the things Uncle Sam asks us to do willingly to help with the war efforts.” (Walter).

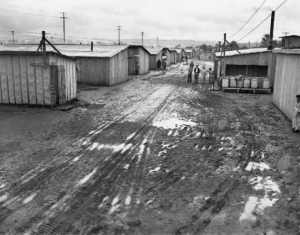

Eatonville’s Japanese population was taken to Minidoka internment camp in Eden, Idaho after spending time at “Camp Harmony.” It is a stark contrast from the green forest and foothills of Mt. Rainier.

“Dust was everywhere, in the house, in our clothes, in our bed, and in our mouth. The wind blows it up in clouds, and it’s very uncomfortable to say the least. When the wind blows, the dust comes in through the slightest crack, especially around windows and doors. But now, the Engineering Department has been sprinkling the streets and eventually the dirt will be packed down. The bright spot of all this dust is the grass planting program, as soon as water is available.”

Chet Sakura September 5, 1942 (Walter)

In October, Sakura and several others went to the beet fields, where they averaged $5 a day. In his letter to the Eatonville Dispatch Sakura said, “I would still rather be in Eatonville working as a common laborer at $6.60 [sic]. I often think of work and things back home and at the same time compare with the locations we’ve been settled in.” Sakura had been a radio repairman in Eatonville (Walter).

Finally, Chet Sakura was allowed to use his radio skills. Here he is posing for photographers with the caption reading: Radio Repair Shop.

During their time at Camp Minidoka, the Japanese ran schools, governing committees, social functions, weddings, funerals, and churches. They tried to make life as normal as possible.

Several Japanese enlisted for duty in WWII. The main fighting group of Japanese was the men of the 442nd. They were a self-sufficient fighting force and fought with uncommon distinction in Italy, southern France, and Germany.

The unit became the most highly decorated regiment in the history of the United States Armed Forces, including 21 Medal of Honor recipients. The families of many of its soldiers were in internment camps.

At war’s end, the camps closed. To return to home “someday” never came for Chet Sakura, or other Eatonville Japanese who wished to return to town. Upon investigation they found their return would not be popular with some of the local people. An “Anti-Jap Association,” with headquarters in Sumner, had a branch in Eatonville. Even the veterans of the war entitled to their former job status, did not return (Walter).

8 responses to “Eatonville Evacuation: The Removal of the Japanese”

My grandfather (William Hill) managed the Standard Oil depot in Eatonville at this time. He told me that the part of town where the Japanese lived was colloquially referred to as “Jap Camp.” One of the Japanese mill employees, a Mr. Naido, was a very good friend of my grandfather’s. When the internment started, the Naidos decided to try their luck back in Japan rather than being sent to a camp. After the war, my grandparents and the Naidos got back in touch again. Mr. Naido stayed in Japan, where he became a successful businessman. I have a beautiful tapestry that he sent to my parents as a wedding present. My grandmother always talked about going to visit them, and I was hoping to accompany her, but it never came to pass. I think she was afraid of being so out of her element, even in the company of old friends.

LikeLike

Thank you for the touching story!

LikeLike

[…] War II and the Japanese internment touched Eatonville in the 1940s. Abbi Wonacott shares these photos over her mother’s (Lois […]

LikeLike

Wow. Thank you so much.

LikeLike

This is fantastically detailed. Amazing. Thank you so much for sharing!!

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

We go to the Eatonville cemetery to visit my husband’s grandparents’ grave. We always stop and spend a time at the Japanese graves, and are glad to find out why and where they were. A sad time for them during WW II, when home was far away from Eatonville. Even sadder when they were not welcomed back where they had lived many years.

LikeLike

I just learned my father (passed this year at 87) was born in Eatonville. His parents were Asano Fujiwara (Kirihara) and Yoneichi (Frank) Kirihara. Just wondering if anyone knew of the Kiriharas there.

LikeLike